Featured Authors

Bruce Ward

Chael Needle

Doc Phineas

Hank Trout

Steve Carr

Sumiko Saulson

Trinity Adler

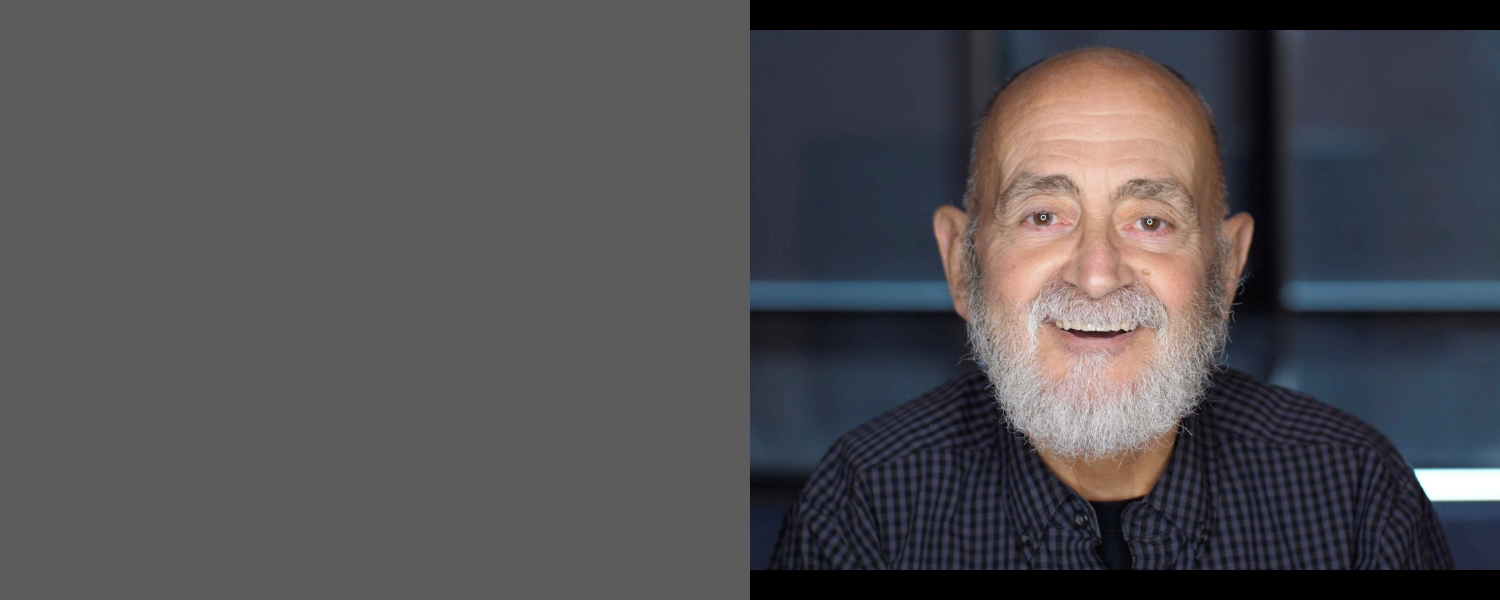

Hank Trout

Hank Trout is a writer and editor, a 40-year resident of San Francisco, and a 31-year long-term survivor of HIV/AIDS. In the 1980s, he edited Drummer, Malebox, and Folsom magazines. Currently, he is Senior Editor, columnist, and feature writer at A&U: America’s AIDS Magazine, the country’s oldest AIDS magazine. A five-time nominee for the prestigious Pushcart Prize for writing, he lives with his husband Rick Greathouse. This is the fourth year that Hank has contributed to the Art & Pride Exhibit.

Celebrating Community – and Hope

by Hank Trout

We’ve been here before.

This is not the first time our community has lived through a pandemic, fearful for our own health, worried that our friends and lovers and family would fall victim to an insidious virus. Nearly forty years ago, another virus invaded our community, invaded our bodies, and decimated a generation. We are all too familiar with the lurching incompetence of an indifferent government; we know too well the long wait for an effective treatment or a vaccine; we’ve seen before the ignorant, racist push to blame someone; we’ve heard the ignorant proclamations of “men of God”; we remember watching the body count steadily rise and rise and then rise some more so that we became inured to mourning, numb to the pain. We remember learning to live with grief.

During the AIDS pandemic, we lost so much. So many young lives brutally snuffed out, so many friends withered and gone, so many lovers cremated or buried. The loss to the arts alone is unfathomable — so many plays that will never be performed, songs that will never be sung, artwork that will never be painted, photographs that will never be printed, leaders that will never rise. But worse, we lost our innocence. The first brush with freedom and liberation that we cherished in the 1970s came crashing down around us in the 1980s and ‘90s, much as the economy is crashing around us now.

But through it all – through the pain and the tears, through the grief and the chaos, through the hospice visits and the memorial services, through the bigotry and hatred that the pandemic intensified — no matter what we lost, there are two things we never gave up.

Our Pride. And our Hope.

We have earned our Pride. From the Mattachine Society, established in 1948 by Harry Hay and the Daughters of Bilitis, established in 1955, through the 1959 riots at Cooper Do-Nuts in Los Angeles and the 1966 riots at Compton’s Cafeteria in San Francisco, LGBTQ people have fought, sometimes physically fought, for the simplest of rights — to assemble without harassment, to live free of the threat of violence, for adequate healthcare, to love whomever we choose. The Stonewall Riots in 1969 galvanized our community like never before. Along the way from Stonewall to the present day, we have fought for and won non-discrimination laws at the local and state level, ensuring our access to housing and employment; we have fought for and won the right to serve openly in our country’s military; we have fought for and won the right to marry whom we love. Faced with the horrors of the AIDS pandemic, we rose to our highest heights of compassion — even when mourning our dead seemed like a full-time endeavor, we made time to care for our sick. The artists and performers among us lent their time and energy and talents to raising hundreds of millions of dollars for research and proper care. We opened our hearts and our homes to those who needed us most. With ACT UP and other organizations, we marched and fought for access to medication — and won. And for the first time in our history, lesbians and gay men came to recognize that we are one community, one Tribe, as our lesbian sisters marched to the front lines of the fight for their fallen gay brothers. We became the gold standard for compassion and fortitude.

For fifteen years, 1981 through 1996, we fought for our lives – and spent the next twenty-five years fighting for our right to live.

And through it all, we emerged with our heads held high, our spirits renewed, our community intact, and our hope justified. Our rainbow colors never faded, our solidarity never waned, and our love for one another never faltered.

We have every right to celebrate our Pride!

When Harvey Milk told us, “You gotta give ‘em hope!” we understood immediately what he meant. Hope for a gentler, kinder world where we could live safely and love freely; hope that LGBTQ youth could live free of the threat of violence and hatred; hope that all of our tribe, here at home and around the globe, will someday be spared the condemnation of the religious, spared the indifference and hostility of governments, spared the prejudice and ignorance that we Elders in the Tribe have fought against for many, many decades.

That Hope still lives. In these days of social distancing and sheltering in place, we are sustained by our Hope — we know that someday we will be together again. This too, as they say, shall pass. We know that we will emerge from this pandemic together. We know that soon we will be able to gather and celebrate and parade again, with our heads held high and our rainbow flags waving even higher.

Community, Pride, and Hope are in our DNA. We will never let anything tear our Community asunder; we will never let anyone diminish our Pride; and we will never, ever give up Hope.

Trinity Adler

Trinity Adler is an author from Carmel, California. Her poetry and stories have been featured in Written Across the Genres, Clockwork Wonderland, Cairn Terriers in the Movies, Life in Pacific Grove, and on numerous blogs and websites. Her poem Twenty Capitol Crimes was featured in the 2019 Harvey Milk Pride celebration in honor of Gilbert Baker. Her website is www.TrinityAdler.com. She writes a column for the Central Coast Writers Branch of the California Writer’s Club. She’s a filmographer and curates a history of Cairn Terrier films at www.Cairnterriermovies.com.

Friends

by Trinity Adler

I opened the car door

He stood up

We hugged

It’s been such a long time

He whispered in my ear

I have AIDS

I don’t have to stay if you’re nervous

He waited

Studied my face

I smiled

Then asked

What do you want to eat?

No sushi or raw meats

It’s dangerous

I mean for breakfast

He laughed and shook his head

Oh, I’ll eat just about anything with coffee

You can make the coffee

He hugged me again

We took his bags inside

I cooked pancakes with blueberries

And served them up

On the best china

Doc Phineas

Doc Phineas is known as “America’s Favorite Professor “on the History Channel’s hit TV Show PAWN STARS. DOC is a die-hard San Franciscan who holds a Ph.D. In Archaeology, a University Professor of 50 years, a TV Reality Star currently on Mysteries At The Museum, Jay Leno’s Garage, Haunted Hospitals, and the new star of TOUCHED. He is author of 5 books in which his latest “From India With Love” is a Best Seller. He established the first Yoga Centers at Caesars Palace and The Mandarin Oriental Hotels on the Las Vegas Strip where he has taught Sir Elton Jon and Cher. He stars in the Broadway Show ALICE on the Las Vegas Strip where at 70 he us wowing crowds singing and tap dancing! Here is Doc’s first memory of his first day living in “The City”.

My First San Francisco Friend

Doc Phineas

I am on my way to my new pad in the City of San Francisco, an impeccable Victorian in Noe Valley. My B.A. degree Magna Cum Laude President’s Scholar from San Jose State proudly on the wall, I take my new Canon camera, a graduation present from my parents, for a stroll down the Castro. Here I am, in the most beautiful city in America, surrounded by brightly painted Victorians, window boxes cascading with flowers, and the most handsome men smiling at me as I walk down the street. Click, click, I keep taking pictures of the amazing architecture, the colorful flowers, and the handsome guys everywhere!

My first trip down the hill and I arrive at 18th Street. I finish a roll of film. Twenty years old, hot to trot, a male model signed to the best agency on Union Square and enrolled in Grad School at UC Berkeley. I am on Cloud Nine walking in a sea of men, street musicians, fantastic music blasting from the bars, cool shops, sidewalk cafes, and so many smiling faces! I see a sign, Castro Camera, and I have a roll of film to develop. I walk in.

“Well hello, and how are you? Come in!”

The man with the friendly face just envelops me.

“I have a roll of film.”

“You certainly do! I’ll take that and here’s a fresh roll, a gift, on the house.”

Smiling back, I whisper, “God I love San Francisco!”

“Are you new to the City?”

“It’s my first day…”

“Well young man you must be initiated. Can I buy you a drink?”

“Man I wish, but I am not 21 yet…”

“Ah baby, well then, can I buy you an ice cream cone?”

“Now you’re talkin’! I will never turn down ice cream.”

I can’t believe how cool this man is who will just put a sign in his window and walk me down the street to treat me to ice cream. As we are walking, I share that I am a guy from Kansas, freshly graduated with a B.A. degree, signed to a modeling agency, and on my way to grad school. Secretly I love his smile. I tell him he is my first friend in San Francisco, as I sit devouring a cone of cookies and cream.

“Well, since you are eating ice cream Handsome, you will never forget my name. I am Harvey Milk… and I could watch you lick that ice cream cone all day long…”

We are laughing and Harvey Milk is my first friend in my new home where I am finally FREE TO BE ME!

Anytime I walk the Castro, my first friend runs from his shop to hug me, to always inquire how I am. When I have my 21st birthday, Harvey buys me my first drink. How many young men does the King of Castro welcome to a life of freedom, dignity, and fun?

Postlog: I had my wonderful Victorian in Noe Valley from 1972 to 1989, until my life in Hollywood became too demanding. Then, I could no longer sneak away to the City. I will always remember Harvey, my first San Francisco friend.

Steve Carr

Steve Carr, from Richmond, Virginia, has had over 400 short stories published internationally in print and online magazines, literary journals, reviews and anthologies since June 2016. He has had six collections of his short stories, Sand, Rain, Heat, The Tales of Talker Knock and 50 Short Stories: The Very Best of Steve Carr, and LGBTQ: 33 Stories, and The Theory of Existence: 50 Short Stories, published. His paranormal/horror novel Redbird was released in November 2019. His plays have been produced in several states in the U.S. He has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize twice.

His Twitter is @carrsteven960.

His website is https://www.stevecarr960.com /

He is on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/steven.carr.35977

The Birds Weep

by Steve Carr

The air is thick with the scent of pine. Rays of purple, blood red and golden yellow are fanned out across the twilight sky. Kyle walks among the trees holding a bouquet of wilting lilies. Lost, he searches for signs of the path he wandered away from. As the sun sets, owls hoot from their perches and hawks screech as they circle about in the oncoming night sky.

At a fallen pine tree he sits on a branch and tries to remember the direction he was going. He puts the flowers to his nose. They have lost their scent. He watches the sparrows, juncos and blackbirds as they fight the cold wind on the way to their nests. The cry of a loon from a nearby lake reverberates through the forest. It gives him a sense of direction. The lake is near his destination.

Night sets in fast. The black sky is suddenly splattered with clusters of stars. The coos of mourning doves fills the air. He walks on, sensing he is now on the right track. When he reaches a clearing among a grove of sycamore trees he stops and gazes at the small group of cemetery headstones surrounded by a black fence.

He passes through the fence and finds his grave. He lays the lilies on the mound above his coffin. As he slowly disappears into the earth he knows that now that his last wish was granted to wander the Earth one final time, he would not return. He hears the birds weep.

Chael Needle

Chael Needle is a writer, editor and teacher living in Astoria, Queens. He is Managing Editor of A&U, a national nonprofit HIV/AIDS magazine.

Human*

by Chael Needle

Human*

with an asterisk

to you we are

because of where we kiss.

You let us

borrow the moniker

with conditions

& curfews.

How

very

generous?

We don’t need

your annotation,

your extra explanation,

your small-print footnote

to the story that you wrote,

a codicil

to your might and will,

an amendment

that says we are all the same

but always different.

Always bent.

Human’s not all that

to begin with,

making order

out of nothing and something

heaven-sent.

Matter sucks!

Spirit rules!

Chain, chain, chain

Chain of fools.

Human.

You can have it back.

We’re more and more sure we can’t

salvage that.

But let’s keep the asterisk.*

___________________________

* It’s a guiding star

lets us know who we are

n’t.

A Day

Fiction by Chael Needle

With a touch of his finger, Trace checked the weather on his phone, but the app only floated a pixelated temperature beneath a sun icon. It promised 52 degrees. In March, with a brisk wind, that could easily feel like 38. He wanted to know how cold he would feel.

He had to guess at coats, as he prepared to go into Manhattan later that morning with his friend Ade.

He chose his light winter coat, cut like a blazer but with a heavy lining beneath the dark-maroon wool exterior. He decided against a pair of gloves and a tuque. He could always take off his coat and carry it around if hot, but he could not trundle around carrying his coat, and gloves, and tuque. He would look like he prepared for the worst instead of the best.

As he pulled on his coat, he realized that one of his scarves still lined the interior of his right sleeve. The scarf clung to the length of his arm. It bulged like a vein.

He took off his coat and pulled the scarf out of the sleeve with a magician’s flourish.

His grandmother had knitted this scarf for him. Stripes of color, a fuzzy rainbow, repeated down its length, but he was convinced they had nothing to do with Pride and more to do with bringing together dwindled skeins of yarn not used for her main projects. But maybe, he mused, that had everything to do with Pride.

When his grandmother died, last August, he had been commissioned by his mother, thousands of miles and three airports afield at the time, to make the journey—What is it? Twenty minutes to midtown from Astoria?—to clear out her apartment and salvage family heirlooms. He found nothing of the sort. Nothing to sort. Instead, he had found her slippers threadbare, her underwear dingy from handwashing. He had found her prescriptions outdated or not refilled. He had found her pantry stocked with food, but of the oddest kind. Though she was not Jewish, she had boxes and boxes of matzo and macaroons, and jars of gefilte fish. They all bore price stickers that had been slashed, severely discounted after one holiday or another.

He should have checked on her more than he had, he realized. He knew she was poor but her apartment, once chocked with furniture and bric-a-brac and lamps and books, the unexcavated strata of her life, had become as spartan as his. She had had to pawn everything of value. He found the tickets in a crystal vase near the door and sealed them in an envelope for his mother to decide whether or not she wanted to buy back the familiars of her childhood. His mother never did collect them.

As for the scarf, he would have never seen it had she not died. He had found the scarf packaged for mailing on her sewing table, where she made baby clothes that her church sent abroad to the children of earthquakes and tsunamis. The mailer had been addressed to him, but he had not lived at that particular address for years. He had stood there, unwrapping it from a rough swaddling of opaque white tissue paper. In the pale light that swooped under dark storm clouds and clung to the window, he pressed its soft folds to his face, curious if he could sense her fingertips in the stitching.

For these past two years, his mother had wanted to place his grandmother in senior living, but she had resisted and refused. Her daughter traveled for work, photography assignments that took her to Seoul and Amsterdam and Durban, and couldn’t be bothered to press the issue.

Every time Trace visited after that skirmish, his grandmother kept bringing up assisted suicide. How it was legal in Vermont. Would he take her to Vermont if the day came when she was forced to leave her apartment? Help me, she implored.

He had tried to quell her fears, assure her that her good health augured no drastic change in her living arrangements for the near future, but, finally, he had to promise her that he would help her carry out her plan. Yes, he would drive her to Vermont.

She reminded him of his promise every time he visited. Trace visited less often.

He could not bear to think about her death, his hands on the steering wheel on a road that twisted through the night, driving her through the dark-capped mountains of Vermont as she craned her head out of the window to look at the stars one last time.

(Click here to see the full fiction)

He draped the scarf over the highback wooden chair as he buttoned up his coat. He told the scarf to be patient. He would not be long in buttoning up his coat.

He thought of phoning Ade and cancelling, but he couldn’t disappoint him.

If it were any other day, if it were anyone else other than Ade, he would have stayed at home. He would not have cared about the weather. He would have ordered sushi from Sakura. He would have masturbated himself into oblivion and then cursed himself that he had not rationed enough horniness for an evening hookup. Who was he kidding? If he wanted a sound spanking, that usually meant leaving the apartment and taking the N into Manhattan and trudging through the puddles and slush and ringing strange bells.

Even the promise of sex no longer motivated him to engage with the world as it once had. He had abandoned his morning calisthenics months ago and chubbiness had returned. He went unshowered for whole weekends, his thick red hair unkempt. No one inspired him anymore. He didn’t care, anyway. He had yet to find a man who could deliver bum smacks—as hard, as swift, as intense—as Ade could. His hand could make Trace as hot as a grunting radiator. They had not played together for months and, if Trace had his way, they never would again. He did miss Ade’s stern voice, his own splutterings, the breathless kisses of their milky finales.

As he pulled it from the chair and wrapped it loose around his neck, Trace apologized to the scarf for having not given it more to do that winter. He could not bear to tell the scarf that it might no longer be winter. The scarf had only seen one winter. And it had been a winter whose blizzards had melted quickly. He wanted to tell the scarf not to worry. Colder days were ahead.

The scarf remained mute. No answer. No ‘It’s okay.’ It was hard to guess exactly what the scarf might be thinking.

He had never worried until today what the scarf would do all spring and summer once he stowed it away. In its practical plastic tub, the scarf, along with the other scarves, and gloves and tuques, would become a bed for his spare light bulbs. Would the scarf recoil, its colorful threads touching curved glass and not skin? Did the scarf feel repulsed, doing nothing? Did it have a sense of its purpose? Did it know its mission was unfulfilled? That it was supposed to be providing warmth instead of hibernating in a tub? Who knows? Maybe it had never wanted to be a scarf.

He had bought the tub at the bed-and-bath store that day when Ade, still able to walk unassisted, had yanked him up to Steinway to go shopping.

Ade had goaded him to stop living in a half-empty apartment, dusty swaths of space between his bed in one room and his computer desk in another. Create a home, for god’s sake!

Ade had come over one night to drop off a borrowed book and found that one of his sculptures he had given to Trace had been ill-treated.

“That’s what you do with my creation? You place it on the floor?”

“I’m sorry.”

“Look, it has a ding in it.”

“Where?” Trace squatted. “I didn’t do that!”

What Trace had tried to pass off as Zen, Ade exposed as indifference to self-care. Jeremy left five years ago! Move on with your life!

Trace had had to start over after that break-up. “You’re a cold, fucking bitch,” Jeremy had said by way of ending an argument, and the next day, each time Trace turned around with a plea for him to stay, another piece of furniture, another framed poster, another clock had disappeared. Jeremy had left behind only one thing, a bottle of painkillers for his foot that he had never used, and Trace would open the medicine cabinet and stare at it, wondering if the pills were enough to anesthetize his grief once and for all.

The apartment had remained as bare as a tomb, as New York apartments of the young do, but the difference was he was not out eating dinners at neighborhood restaurants nor gallavanting at clubs. Trace spent most of his time there, with absence and anger, his quiet roommates who always washed their cereal bowls and kept their music low.

During their shopping trip, under Ade’s watchful gaze, Trace bought a tidy couch and coffee table, DIY shelving, some dressers, and soon got into the spirit of inventing his future. He imagined careful appointments around the apartment. A set of Hiroshige’s “14 Famous Views of Edo” that he found in the bargain section of the bookstore would look great on the wall leading into the kitchen. Candles on wrought-iron spires would complement the black-oak furniture in the living room. He bought pillows, in purples and reds, which he would pile onto his bed.

He did not let on to Ade that he might not be fully on board. But he realized the trick that could be played. If it looked like he cared about himself, others might care about him.

After a long, three-block walk, overheated by a sun that seemed to follow him like a spaceship’s tractor beam, he pressed the buzzer he had first pressed five years ago, and Ade answered through the speaker with his usual gruff line: “I don’t want any!”

Trace leaned in with a smile that no one could see: “I wasn’t offering any.”

He grasped the doorknob in anticipation. The buzzer that released the lock bleated loud and harsh, but to his ears it was as lovely and soft as “Open sesame.”

Ade had managed to dress himself—in all black, his favorite uniform obeying no hour of the day nor season—without the help of the home health aide, who had now left for the day, dismissed to find some other quiet place to gossip on her phone.

“It’s cold?” Ade asked, looking up from the coupons he had spread across the surface of the tray that extended from his computer desk. Soon, as soon as he left for the nursing home, they would be worth nothing.

Trace slipped off the scarf and bundled it with his coat on the chair. He could leave the scarf behind, but then he worried that it probably would feel orphaned. It wouldn’t understand that he was coming back. “No. I guessed wrong.”

“I don’t want to go if it’s cold.”

“Yes, yes. We’d go if there was a blizzard out.”

Trace kissed his cheek. Ade had titled his head in anticipation.

“Yes,” Ade agreed. “You’re right.”

“You look very handsome.” Ade always waited, impatiently, for one of Trace’s compliments. They were only courtesies, he guessed, as cheap as diner mints in a wicker basket near the register, but he still liked to suck the peppermint flavor off of their surfaces.

Trace stopped at the shelves, as he always did, to look at Ade’s sculptures, the ones not in storage, small twisty rough-hewn stone things that had been tortured, like bonsai, into beauty. Ade had worked for years but he had never made much headway. He had never had his day in the sun. No gallery representation. No solo shows of any repute. Trace had wondered why he had kept at it, long after he had realized he had failed.

Ade looked at the blank monitor to check if he had turned his computer off.

It was only 10:30 a.m. but Trace thought they should eat lunch before they left. “What kind of soup—?”

Trace looked in the cupboard, muscle memory from his volunteer days. Soup can after soup can. All low sodium. He thought of his grandmother sitting down to her daily Shabbats and Seders. He almost cried.

“I’d rather have corned beef from that deli on 5th Avenue.”

“It’s so expensive—that deli. It’s become a tourist trap.”

“I have coupons.”

“Won’t going up those stairs be too much bother?”

“I can manage.”

“I did make reservations at that Nigerian restaurant in Hell’s Kitchen.”

Ade chuckled at the nostalgia Trace thought he harbored. “Igbo or Yoruba?”

“Oh, I didn’t ask!”

“I’m just teasing you.”

“You’re impossible.”

Trace touched one of the sculptures, where the smooth stone bled into the rough.

“I want my corned beef. You said it was my day. Didn’t you say it was a day just for me?”

He pressed RETURN on his keyboard to see if his computer was still on.

“Yes. You can have as many days as you want,” Trace lied.

“No. I can’t. Once I step foot in that nursing home, that’s it. It’s all about what they want, not what you want. They say it’s all about your schedule, but it’s really all about their schedule.”

Ade thought he would be able to stave off the nursing home for another ten years, when he would be eighty, but his legs had deteriorated more rapidly than expected. His social worker had thought it would be too taxing on the home health aides if he stayed in his apartment. Yes, it would be a tragedy if they missed one of their TV judges having to help him bathe. He wanted so badly to say fuck off to his social worker but he had no husband, no savings, not even enough for an electric wheelchair, no pension, no private insurance. Perhaps his son had been right to disparage his life choices, starting with an exorbitant loan for art school it had taken him thirty years to pay back.

“I have the whole trip to your nursing home mapped out on my app,” Trace said, showing him the face of his phone. “It takes one hour and forty-eight minutes on the N. Shorter if I switch to the Q mid-trip.”

“I don’t expect you to visit me at the nursing home.” Ade had been disappointed that nothing closer had been available, that he would be jettisoned to a far edge of Brooklyn he had never even visited.

“Or it will take me forty-five minutes if I hire a car.”

“Too expensive.”

“Don’t be silly. I’ll visit.”

“Remember when that art show about queer desire was at the Brooklyn Museum? We kept saying we’d go and we never did?”

“That was to see some exhibit. This is to see you.”

Ade let him have his fantasy. He knew this was the end. Trace might visit, but to do what? Stare at the ocean? Crack wise about the nurses? Watch CNN on a giant screen TV like they were grounded at the airport? Make dreamcatchers in the friggin’ arts and crafts room?

Trace tempered his idea: “I know we might not see each other very often, but why do you have to be so—final? You’re impossible.”

“It helps nothing to pretend otherwise.”

Ade had grown up in a different generation, so he accepted that some relationships ended. He would mourn, of course, and miss Trace, but he could move on. He didn’t hold stock in this new world that promised the hope of endless connectivity. People fell apart.

Ade picked out a couple of coupons and stashed them in his shirt pocket. “It’s a trick. They pile you into the nursing home as if it’s a lifeboat. But they don’t tell you the lifeboat is the one that’s sinking. It’s a deathboat.”

Trace laughed. “Will you stop being so dramatic?” What he thought was: Please, never stop being so dramatic. “We can still talk about moving in together.”

Ade looked at the monitor again, and wiggled the mouse. Sometimes the computer only pretended to be asleep.

“That’s an insane thought, even for you.” Ade at one time had daydreamed about taking care of Trace, not the other way around.

Trace ignored Ade’s attempt at humor or derision, he couldn’t tell which. “I have the room. I’m on the first floor.”

“You take me in, but my own son does not?” He had not heard from his son since he told him he was set to go to a nursing home.

“You hate Long Island!”

“I hate disrespect even more.”

“He loves you.”

“What difference does that make?” Ade let his anger deflate as he glanced up and saw that Trace was trying, and trying very hard, not to cry. “Besides, I wouldn’t want to interrupt your sex life.”

How simple, thought Trace, to be saved by a laugh. “Ha! I haven’t had sex in weeks.”

“Tragic! Try six months.” Trace bristled at his calcuation, the unintended mirror held up to the one who decided to end things. Ade pressed on. “What about those spanking parties you’re so fond of?”

“Stopped for now. And I’m thinking of calling a moratorium on all hook-ups. All sex. The last time I hooked up—younger guy, right? He walks in the door. No talk. No one can even say hello anymore. Just a lusty grunt: hey.”

Ade rose and began slipping on his spring coat, one arm at a time, so Trace hurried on with his story as he helped him. “So we have sex. The sex is…sex. And we’re finishing up. I’m lying on my back. My eyes closed. He is straddling me and jacking me. I’m into it. I’m enjoying it. But I open my eyes and the guy is looking at the slideshow on my monitor. He’s jacking me like it’s a chore.”

Ade chortled. “I’ve handled your manhood. It is a chore.”

“Ha! Sorry it’s so laborious for you.” Trace faltered in his laughter, the misspoken present tense, remembering why they had stopped their fun. When Trace was mourning his grandmother’s death, sobbing randomly, Ade had halted mid-spank when Trace had blurted through tears plumper than his erection: Help me, he implored. Ade had asked him if he was okay. Embarrassed, Trace told him to forget it, fled, and never laid himself across his lap again. To his mind, Ade had betrayed the rules they had set up. There was always a beginning, a middle, and an end. Admonishment, a roasting, coddling. A solid and dependable plot. The true source of his tears was no business of Ade’s.

Ade smiled. “What were the slideshow pictures of?”

“That’s not the point—” Trace now regretted telling this story, realizing it had been spoken from the mouth of a friend but heard by a lover’s ears. “The arty ones my mother took at that beach in Rio.”

Ade hummed. “All those men—so humpy in their skimpy trunks.”

Humpy. It was one of Ade’s favorite words when describing the beauty of men.

Funny how one word in the right mouth could send one into an apoplexy of desire, thought Trace. He had kept safe in his heart certain words or phrases from the men he had loved. Not only the words but how they had been said, the timbre, the context. Even Jeremy’s You’re impossible. He had woven them into his speech. Of course, no one knew their histories except him. No one knew he was calling them up like spirits when he spoke them.

But he didn’t want to adopt Ade’s word. Not just yet. They had one day left together.

“I know the point,” Ade said, not wanting Trace to think he had forgotten his story. “But that was one man out of how many…?”

“Yes, okay, but there’s a general sense of no-talk, just-sex,” Trace bemoaned. “It just seemed like when I met guys at Phoenix there was more of a sense of a connection.”

“So go back to Phoenix.”

“That’s changed too. Everyone is looking at their phones now.”

“You don’t have a sense of connection online?”

“No, not really.”

“Then meet for a bubble tea first.”

Trace was pleased, and unsurprised, that Ade had remembered he liked bubble tea. He had only mentioned it once.

“The only ones who want to meet first are the ones who want the option to reject you.”

“Or the option to make a connection. You can’t have it both ways. Search for what you’re after somewhere else then. Start your own spanking party. Don’t wait on anyone else to host your desires. Are you listening to me?”

“Always.”

“No, you’re not. You’re as bad as my son.”

Trace disapproved of the comparison but did not challenge it. “I just don’t want to let the cold, lonely streets of New York into my heart.”

“I don’t know how to avoid that with strangers. Or with friends. Or family. The heart has its cracks where the wind gets through. It’s an ill-made door. We’re all cold.”

“But I’m super-cold. I’m a ‘cold, fucking bitch,’ remember?”

“Then you should say that up-front.”

“Oh yes. A fine way to start a romance. ‘Hi, I’m cold as fuck.’”

Abruptly, before Ade could respond, Trace shifted to a leaving-the-house checklist—subway pass? stove off? iron off?

He did not want today to be anything but mundane. He would resist all epiphanies. He would learn nothing. He was determined that today not become a “memory,” but slip into the stream of their ongoing friendship. He wanted today to be nothing special, and, so, special.

Ade checked to make sure his computer was off one last time.

His door locked, Ade tackled the one flight of stairs to street level. Each step was a jumble of clankings and breathing as Ade maneuvered his forearm crutches. Trace loped a bit ahead of him.

The downstairs neighbor came home. She paused, adjusting her thick-rimmed glasses. “I’m going to miss you, Ade.”

Ade did not answer her, unaware that the news of his departure had made the rounds.

“If there is anything I can do. Collect your mail or—”

“Thank you,” Trace answered, much more softly than she was shouting. She looked at him and smiled, before she disappeared into the darkness beneath the stairs.

The kid from upstairs came home. He bounded up to the first step and then stopped short, seeing his way was blocked. He huffed.

Trace refused to leave his post. He was not assisting Ade in any physical way. He was there to catch Ade if he stumbled, he supposed. Otherwise, he imagined his energy afforded Ade a force field of protection.

Ade hated this attention. Everyone who wanted to help, even Trace, seemed only to be around minutes out of the day. Their concern was dwarfed by the hours he had to go it alone when there was not a meal to make or meds to swallow. He read mostly, books he bought for fifty cents or a dollar from the Greek woman who parked her cart under the N. Sometimes he fiddled around on-line, taking virtual tours of museums in countries he would never visit. Mostly things remained undone. Query letters to galleries remained unwritten. Clothes remained unfolded. Dishes unwashed. Relationships unmended.

The kid backtracked into the vestibule and argued with his mother over the intercom. When he said “the old man,” Trace wanted to scream him into nothingness.

Ade motioned for Trace to descend ahead of him with a little grumble and a flick of his let-handed crutch. “You’re cramping me. I need the whole stairs.”

Franco, his neighbor from across the way, intruded next. The dark-haired man carried a cardboard tray laden with two tall coffees and a bag that smelled like toasted bagels.

Trace smiled to himself. Ade had once called Franco humpy.

“Ade, you’re getting out!” He flexed his lightly whiskered grin as if it were his bicep.

“We’re going to see his favorite painting,” Trace replied, leaning against the wall, hands behind his back.

Ade grimaced. It sounded silly when Trace put it like that. Sentimental. Childish. Ade thought of the trip as practical, something that needed to be done, like choosing a burial plot. He had hated that whole fuss. He simply needed a chunk of earth. What did he care about the prospect? If his son and his daughter-in-law and his grandchildren had a bench to sit on and a pretty view?

“It’s my day. I get to do whatever I want and everyone has to do what I say,” Ade announced, glancing at Trace, as he steadied one foot on a step.

“It’s your birthday?” Franco asked, befuddled.

“The exact opposite.”

Franco looked to Trace, who refused to explain or apologize or anything.

“I’m sorry about your coffee. I know it’s getting cold while I am taking my sweet time.”

Ade smiled at Franco. He loved to flirt with him, this man whose chest was meant to be, his bosomy pecs encased in a tight black T-shirt. In his younger days, and really not so long ago, Ade could have gone toe to toe with Franco.

“It’s all right. I’ll let Marissa know we are out here,” Franco said, texting his girlfriend with his free hand. She almost immediately opened the door and stepped to the top of the stairs and perched there.

“We’re having a picnic in the hallway?” she asked.

“Yes, a picnic brunch,” Franco agreed, as he halved what he carried, removing his crumple-foiled bagel from the bag and his coffee from the tray and setting them down on the bottom step.

“Ade, could you pass Marissa her bagel and coffee?” he asked, extending the tray.

“You’re a smart, beautiful man, Franc-o daddy-O,” said Ade, in response to this sweetheart gesture. He freed his right hand from his crutch and extended it to the proffered tray.

“Yes, he is,” Marissa agreed, though Ade could only hear, not see, her smile. “But hands off. He’s mine.”

“But can you handle him, my dear?”

“Oh, I can handle him. Don’t you worry about me, Ade.”

Franco grinned, blushing.

Franco, Marissa and Trace all watched Ade grasp the laden coffee tray. More than one of them worried about the imbalanced weight of it. But Ade’s hand did not tremble. In a slow gesture, his arm traced a wide arc, as if he were ushering someone into a secret garden beyond a wooden door, or a sparkling ballroom of swooning music, or a high-vaulted cave of torch-lit treasures. Each of them who watched Ade wanted so badly to step forward into the world he guarded.

At Ditmars, one block up, they paused in front of Atomic Wings as Ade rested. Trace grew restless around so many people on their way to somewhere.

“We can still hire a car.”

“No, I’m fine. I just need a moment.”

“At least let’s take a car to the elevator at Queensborough.”

Ade lurched away toward the stairs. These stairs were wider than his apartment building’s, but the flow of passengers made them more crowded and the lanes tighter.

Trace stood behind Ade and watched him ascend. Ade’s body rocked back and forth as he hobbled upward as if there was a jerky metronome within him that was counting out his rhythm.

A girl, perhaps six, stopped beside him and pried his hand off of its grip and started to pull him up the stairs.

Ade stopped and sighed, looking askance at her with merriment in his eyes.

“Aren’t you the helpful one!” he said, pretending she was helping him.

She smiled. Her mother goaded her to leave him alone.

“No, no, it’s good to see someone who is so kind and helpful.”

“She is kind and helpful,” the mother answered, but it sounded more like a directive than a compliment.

“Where are you off to today?” Ade asked the girl.

“The planetarium to look at stars.”

“Ah, when I was a little boy we could actually see the stars in the sky.”

“You could?”

“Yes, Queens was not so bright.”

“The live streams will be on today.” The planetarium syphoned images from an array of satellites.

“Looking at stars gives you absolutely nothing, except perspective.”

Her mother shot him a queer look, unsure if he was going to start down some strange path of discourse. She seemed ready to cover her daughter’s ears.

“Where are you going?” the girl queried.

“We are going to see my favorite painting one last time. Christina’s World.”

“Is she dying?” she asked.

“No, no. Christina lives forever.”

Ade leaned his body against Trace when they were nestled in their seats on the gleaming subway car, clean and empty in the sweep of sun.

“Did you think I would spill the coffee?”

“Actually, I was pretty confident you would not.”

With his left hand, Ade squeezed Trace’s right thigh and watched his fingers tense in their grip, pinching him softly like so much clay. He feared a death that immobilized him. He imagined his deathbed as one where, if he could not speak, he would at least have full range of his gestures—to point, to caress someone’s cheek, to look away. If he were immobilized, he could perform these same gestures in his mind, but that wouldn’t be the same. That would be a death before death. He was not ready to leave the land of gestures.

Trace drifted in the feeling of Ade’s hand on his thigh as he watched him rest his crutches against the shiny metal railing and in a way they disappeared. Trace wondered if the N line was not simply his set of crutches, just of a different kind, but one he refused to use.

“Are you going to apply to that position I emailed you about?”

Trace shook his head. “It’s not for me.”

“What about that newsletter I forwarded to you, about the speed-dating group at the Center? When will you find your daddy-O?” Ade teased.

“Will you stop?” Trace hated that he struggled at both love and work. A success in one might have occluded a failure in the other, and fended off others’ attempts to help him.

“No, I will not stop.”

“You’re impossible. I wanted you to fix me up with your friend’s son, there. The one who just moved back from Florida.”

“He wasn’t for you. You need someone who is going to challenge you. Get you out of your head. Make you come alive again. Some man who can rock your world.”

Trace was reminded that Ade truly cared for him because the truth, from his lips, never hurt.

“Someone strong. Like Franco.”

“Ugh, I do not go for muscle-heads.”

“It’s just a metaphor—his muscular strength. The figurative precedes the literal. We sculpt ourselves and then wait for someone to breathe life into us, even if we have to do it ourselves. We make a promise of what might be. Franco always had his physique but only became strong recently, when he met Marissa.”

“And who will I become?”

“I’m not sure. Have you made a promise to yourself of what might be?”

“No.” Trace paused, eager to reject Ade’s query. He had no clue of what might be. “So what did you promise to yourself?”

Ade ignored his challenge, how close it skated to impertinence. “You need someone who will get you out of that damned apartment.”

“You get me out of my damned apartment.”

“Stop evading.” Ade fished for something in a pocket in the lining his coat.

“What do you need?”

Ade shook his head.

“I forgot the coupons.”

“Check your shirt pocket. You know, it’s my treat. It’s your day.”

Ade found and fingered the coupons, ruffling them with his thumb. The train finally moved forward to its next stop. The short buildings of Astoria, shadows engraved into their facades, rolled past like silhouettes projected from a magic lantern on a wall. “Trace, I lost the only man I ever loved. No, that’s not true. I’ve loved other men. The only man I ever wanted to love. That’s who I lost. Because I didn’t pursue him. That was my problem. Too many men pursued me. I’m not boasting. I just never learned how to go after what I wanted. Who I wanted. I never cast myself as the hero.” The doors zipped open. A throng of passengers boarded, but their jostling presence did not dispel Trace and Ade’s intimacy.

“Simon?” Trace instantly regretted saying his name aloud.

“Yes, Simon. Like you, I was too cold. Closed off. I thought he would come to me, just fall into my lap. But he never did.”

Trace looked elsewhere but the cascade of tears fell everywhere, down every happy face. He had wanted Jeremy, that relationship, and, when it was over, he wanted nothing else. He no longer understood how the world worked.

“I was serious when I suggested you tell the man you want that you are cold, Trace.”

Trace looked at Ade, trying to understand his bizarre advice. “Tell him you are cold from the start. How else will he know that you need warming up?”

Trace looked back to Ade, to bear witness to his affection.

A teenaged boy, clinging to the rail over his head with one hand, hovered and swayed above them like a rescue helicopter over a burning building.

He surreptitiously snapped a picture of them, face to face. He had been able to post the photo to his Wall and tag them with one word, “love,” by the time the train descended into the tunnel under the East River. When Trace and Ade exited the 57th Street station, they had, unbeknownst to them, a bouquet of hearts bestowed upon them by seven strangers.

Inside the modern-art museum, Trace swept right by the bank of wheelchairs. He knew Ade would refuse to be pushed around. Literally or figuratively. Trace laughed to himself.

As Ade perched on one of the cushioned circular benches and watched, from across the hanger-wide, cloud-tall lobby, the ravenous crowd in the adjoining gift shop, all of the visitors preying on keepsakes, something by which to remember their day, before they left the museum for good, Trace snaked through the roped line. He gladly paid the price of admission. He did not press for the senior discount. He would pay triple if need be.

They did not check their coats, though Trace pulled his scarf off of his neck and carried it bunched in his hand. They set off without a tri-fold map. Ade knew the museum like the back of his hand. Third floor—that was their objective.

A few people paused and watched him cross the vast, shadowy floor. With his long, black coat, unbuttoned and swaying behind him, and his crutches flung out before him like bird legs in an even uneven gait, Ade appeared like a desperate, dying crow moving across the floor. Trace walked behind him distractedly, the world’s slowest bride.

Some onlookers, at first, held their breath, reverentially, as if they were watching a performance artist. Some even consulted their one-sheets to check for the title of this piece. Fingers played on the abaci in their mind, trying to figure out its meaning—old age, the dashing man now withered, his younger, somber companion, the contrast in gaits, life, death.

Trace convinced Ade to take an elevator. The escalators were too slender and delicate.

Everyone was super-polite and Trace was very pleased. A rare feeling. The brightness of the third floor, with its tall windows and maze-like white walls, reminded him of the jonquils he had laid on his grandmother’s high-gloss mahogany coffin. At the last minute, at the flower shop, he had remembered—you give people their favorite flower, not your own.

“It’s not here.” Ade stopped, his crutches planted.

“What do you mean, it’s not here.”

“This was her spot.” He nodded to the Rothko that now hung on the wall.

“Might they have put it in storage? Loaned it out?”

“I think it’s left the building once since 1948.”

Trace had never seen Ade this baffled and perturbed. “Let me find out. Let me find out for you.”

He left Ade and walked over to a guard. “Christina’s World?”

“Fourth floor,” he said.

In the meantime, Ade had waylaid a family to look at their brochure and came at him with the same news.

“Fourth floor!” they sang together.

One floor up, they were at first greeted by a wall on which Entering Christina’s World was printed in massive, chubby block letters above paragraphs of explanatory text. Ade closed his eyes, resting, as Trace read. The painting, a simple farm scene in Maine, had been considered old-fashioned at the time it was created. Indeed, at first glance, Andrew Wyeth’s painting seems like a simple work—a young woman sprawled on the wild, unkempt part of the grass in a worn pink dress, gazing up toward a graying house and barn pinned to the horizon. She seems paused in her movement toward what appears to be home, but is home a haven or a site of distress? All tones are muted and her face is turned away from the viewer, and so we do not know the emotions she might be feeling. Thus, they might be every emotion. Critics, for the most part, had dismissed the painting. The action paintings of Jackson Pollock, with their frenetic energy of flung paint and chaotic fever dreams, enraptured the post-WWII imagination. But some perhaps sensed that Christina’s World, too, was an action painting, for Wyeth had chosen as his subject his neighbor, who, suffering from an undiagnosed disorder that robbed her legs of mobility, preferred to drag herself along the ground outside of her home instead of using a wheelchair. It was if she herself were akin to Pollock’s dashes of paint, looping back and forth across a canvas of dried grass. This homespun, rural “action” would never be noted unless one took the time to trace it. Some action is slower but no less engaged or beautiful.

Ade and Trace were directed by a linear arrowing of words down a corridor and around a corner to a dark, boxy room. Light along the far wall indicated where the painting must be. They moved with the crowd but were met with an obstructed view—a pale pinkish block (the color mimicked Christina’s dress, Ade noted) that looked like it could house a small European car had been suspended, about three feet off the ground, in front of the painting, whose top you could see if you peeped over the surface. Some visitors went up along the sides of the block but reported back that one could not see the painting.

Trace guffawed, concerned that Ade’s wish had been ruined by the installation. “What kind of fuckery is this?”

Ade almost cursed, ready to pivot away, but he stopped. He turned to Trace. “Help me sit.”

“What’s wrong? What’s wrong?”

“Nothing. Just—” He eased himself down to the floor.

Trace cradled his crutches loosely in his arm and stepped back as Ade began dragging himself across the floor, under the box, toward the painting.

A guard stepped up alongside Trace, who looked at her, ready to defend Ade, but she only smiled and said, “He’s the first one to figure it out.”

Trace beamed as he watched Ade’s long legs disappear. Of course! How could one truly enter Christina’s world by standing? Was empathy at all possible on two good legs? How could you appreciate her struggle if you kept yourself outside of the space of the struggle?

“I’ve never noticed that ladder before, leaning against the side of the house,” Trace said, once they emerged from the hollowed interior of the box, domed like an apse, having been directed by a guard stationed by the painting through a doorway to a room beyond. Only children, at first, had followed them on hands and knees to gaze at the painting. Before they had departed, adults had followed too. “She is ascending, right? The tone of her dress is the same as the sky above the horizon.”

“Hmmm,” Ade murmured, pretending, not very well, that he had never noticed that. “Did you note the shadow on her back? It’s in the shape of a cross.”

“Oh, yes—”

“Finally,” Ade interrupted something Trace was about to say.

“Finally what?”

“I am her now,” Ade said simply as they walked past other paintings to the exit.

Trace reached for Ade’s hand and clasped it, lightly, the fingers on the grip.

“She was always my hero. I could seek her out and she would let me know that everything was going to be okay. That the world was always limited and limitless at the same time. Now I am her. Or someone like her. But literally, not figuratively. Climbing toward life, sloping up to death. What is death but the final clench of the earth? I hope that when I die, there are things to still figure out. That some mysteries will accompany me to the final one. That I can clench the earth and pull myself toward life.”

Trace squeezed the back of his hand for he had thought the exact opposite until this very moment. “I’m so unclear about so many things.”

Ade turned sharp. His voice was harsh and pointed, echoing. “But you’re perfectly clear about some things and yet you refuse to act. You know exactly what you need to do but you do not do it.”

A visitor moved away from them in protest. Real life was encroaching on the art.

“I don’t know what I need.” Trace tried to lower the volume of the conversation.

Ade obliged, softened. “Needs are not mysteries. Don’t pretend they are. You know what you need. Your heart knows, our hearts know, ill-made or not.”

Trace had let go of his hand by now and was adjusting his coat. He hated himself for ruining the magic, the afterglow, but he had to do it. He was a cold, fucking bitch.

He folded the flattened ends of the scarf over each other across his breast, like a rude guest at a party who wanted to announce that the hosts should curtail their goodbye at the door because he was leaving. Can’t you see? I’m all buttoned up. Let me go.

Trace didn’t like to think so, but a small part of him was heartened by the fact that Ade would no longer be a witness to his life. Ade would live out on Manhattan Beach, on the southern coast of Brooklyn. No one would bother him now. No one would scrutinize him. He could stay in his apartment for days, for weeks, if he wanted. He and the scarf could wait for winter.

The corned beef sandwich lay in tatters on his plate. Ade had not so much as eaten it as disassembled it.

“You didn’t care for it?” Trace had made sure to finish every bite of his $20 egg salad sandwich.

“It’s not the same as I remember. Dry. The pickles are the same.” He munched and munched. “So if you are not going to look for a new job or a new love, why not go back to volunteering?”

“I can’t even improve my own life and I’m going to improve someone else’s?”

“You did mine.”

Trace shrugged. “I volunteered because I didn’t know what else to do, not out of any sense of community.” He flicked a steak fry on his plate, turned it over like a log.

“I won’t miss your apathy,” Ade said without any sort of jest in his voice. “What’s holding you back?”

Trace dismissed the insult because he savored the question, sour as it was.

“I don’t know.” He closed his eyes. “I just want the world to go away. And be still. I’m done expecting anything good to happen.”

“That’s death. You don’t want that. You want to be in the middle of life.”

“It’s hard.”

“Fuck, yes. Life is hard. It would have been so easy to give up on my art but I never did. After all that humiliation, all that rejection, I could have given up. I could have pretended that I didn’t want to sculpt. But I did. I did want that,” he raged. “I don’t want you to visit me.”

“What? Why? I think about you every day.”

“You can’t improve my life. You said so yourself.”

“I admire you. How much I would give to be your son. For real. Not just when we roleplay.”

“You are my son.”

Trace lifted his head, straightened his back.

“Then stay with me. Let me take care of you.”

No one said anything after that. It was enough for them to see the fantasy inscribed upon the air, and then fade.

Outside in the early evening a bitter wind was smashing plates on the dark windows of all the buildings.

“May I have your scarf, Trace?”

“Of course. Cold?”

“Yes,” Ade said. “I need warming up.”

Trace smiled at his gesture. “Do you?”

“Yes.”

He pulled the scarf from around his neck and wrapped it around Ade’s. His hands smoothed down the wrinkles in the scarf. He reassured the scarf. You are going on a new adventure. You will be safe with this man. He knows how to love. “It looks better on you. Keep it.”

Neither of them could think what else to do in this, their last trip to the city. Home did not seem like an option but rather the absence of option.

Winter had returned.

Ade pulled Trace close into an intimate huddle. Trace laid his head against his chest.

“Listen to me,” Ade whispered in his ear. “If you do think of me every day, then every fucking time you think of me, do something. Go and seek difference. Go and seek peace. Go and seek pleasure. Go and seek your man. Your men. Be in the middle of life. If you’re rejected, you’re rejected. If you feel foolish, feel foolish. But seek those moments when you commune. Connect. Share your energy. Create. Create life!”

Trace hugged him tighter. For the first time since his grandmother had died, Vermont seemed very far away. He sobbed, as if they were parting right then and there. They were parting right then and there. Yes, there would be a quick visit some other day, one last Greek take-out, one last rented Jason Statham blockbuster. There would be packing day and moving day. But Trace knew he might never travel out to the nursing home, not because he didn’t want to see Ade but because he feared he would never be able to bring him news of what he wanted to hear.

“Thank you for giving me my day,” Ade said, his finger touching Trace’s cheek to wake him.

“Ade, I want to live.”

“You will.”

Bruce Ward

Bruce Ward, A&U Magazine’s Drama Editor, has been writing about the AIDS epidemic since its inception, and his recently completed memoir chronicles the early years. His play, Lazarus Syndrome, and solo play, Decade: Life in the ’80s, have been produced throughout the U.S. Bruce was the first Director of the CDC National AIDS Hotline from 1986–1988, and was honored by POZ magazine as one of 2015’s POZ 100. He has graduate degrees in Creative Writing from Boston University and The New School. Please follow him on Twitter and IG: @bdwardbos.

A joint reading by Hank Trout and Bruce Ward

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JeE94tqw6Io&feature=youtu.be

Last Dance

by Bruce Ward

Summer 1981. My twenty-second birthday. Midnight. Going to the Anvil, Downtown. The Big Apple! I am a newly minted gay man, exploring this new world, feeling free for the first time in my life, a whole new world opening up to me, a world I didn’t know existed a year ago.

Full moon tonight. Ed, Doug and I take the A train downtown, walk past the trucks parked on Hudson, past the fresh slabs of cow hanging from their hooves. The meat-packing district. Past the punks in their leather with their three-day beards, past the disco bunnies dressed in their hot pink shorts. Sweat pouring out onto a hot August werewolf evening. Past the garbage cans, burning from the day’s heat, sidewalk melting like a grilled-cheese sandwich, the smell of grass in the air. We get closer. Steam emerges from grates like fiery blasts from dragons guarding palace gates. We get to the door. Skinny man in his forties wearing a leather vest looks me up and down and grins.

“Mm Fresh meat.”

He collects five bucks from each of us and lets us in.

Hit by an immediate smell of sweat and poppers and sex, and it’s so dark I can’t really see, but I can sense. I have gone through the looking-glass. The song “Walk the Night” plays with its undulating rhythm and insidious innuendo. And then my eyes adjust to the light. And I see. Hundreds of shirtless men. Young, bald, black, leather, men over thirty years old! Eyes, some with pupils as big as saucers, others hidden deliciously by motorcycle sunglasses. Ed pours some powder into my drink.

Men in white t-shirts, men in leather vests, men in faded jeans, men with handkerchiefs and keys protruding from the left (or right) pockets. I make a note to myself – what is the hankie code? Is left the ‘top’ and right the ‘bottom’, or is it the other way around? It doesn’t matter. It’s my twenty-second birthday and I am here and I’m with my friends and we join the throng of dancing, twirling men. The disco ball above the small, cramped dance floor spins above the sweating, humping, happy men. And there is a flag-dancer on the edge of the crowd, turning and twisting his colored flags. And the ball turns and the flags fly and the men gyrate and everything is colors and music and freedom, freedom, and it is the end of the disco era but none of us know it yet and we dance, we dance, we dance as if our lives depend on it.

The MDA is kicking in and I take another hit of coke. A muscular black drag queen in neon pink hot pants and an Afro nine feet wide stands on top of the bar and lip sync’s “Black Butterfly.” And then another drag queen jumps up and performs “It’s My Life”, and then they share the spotlight for the Shirley Bassey medley. I have no fear, no inhibitions. I approach a cute, muscular guy and shout above the roaring music, “It’s my birthday!” and I take him by the hand and we dance.

And the drag queens perform and the music blasts and the flags fly and the men sweat and the disco ball turns and turns. And it is four hours later and I’m still dancing. I have lost time. But it doesn’t matter. None of it matters. Because I am young and invincible, and life is a fantastic ride into the unknown, and I know I will never pass this way again.

And we keep on dancing, four, five, six AM. Keep on, keep on, seven…eight…nine. And the lights come up and sure enough, it’s Donna Summers’ “Last Dance”.

I greet the morning sun. Sweaty, leather-clad man come swarming into the street that smells of New York City garbage and freshly baked bread. A bunch of us go to Tiffanys on Christopher Street, where the punks and the drag queens drink coffee and smoke cigarettes and eat omelets and whole-wheat toast.

Then I say goodbye to Ed and Doug, and I take a cab uptown with my new-found friend, to his studio walk-up on West 78th Street. And we fuck and we take Quaaludes to come down and we fall asleep, with the late morning sun streaming against his window shades, lying in each other’s arms.

And I am happy. I am happy. Because my life is beginning and I am free, and now is the time to dance, now is this time to shake, to ride, to leap, to fly, to move, now is the time to experience all of this. And I know that someday, someday soon, I’ll want to settle down and I’ll want that body next to mine to be the same one every night, to come home to every night and grow old together.

But not now. Because there’s time for that. There will be lots of time. Now is the time to dance.

Sumiko Saulson

Sumiko Saulson is an award-winning author of Afrosurrealist and multicultural sci-fi and horror. Zhe is the editor of the anthologies and collections Black Magic Women, Scry of Lust, Black Celebration, and Wickedly Abled. Zhe is the winner of the 2016 HWA StokerCon “Scholarship from Hell”, 2017 BCC Voice “Reframing the Other” contest, and 2018 AWW “Afrosurrealist Writer Award.” Zhe has an AA in English from Berkeley City College, and writes a column called “Writing While Black” for a national Black Newspaper, the San Francisco BayView.

Killer Romance

by Sumiko Saulson

People love, you know…

We do love, untrue love,

and there are puppies and kittens,

chubby babies who don’t

have bows…

and arrows…

All trivialized in February

(that was my grandpa’s birthday)

Because they are now

Iconic representations

of an infatuation

More impure than

The sweet-smelling rose

We chose

To kill, to represent…

Incense, sickly sweet

I have allergies

It makes me sick

It reeks…

like a grape-favored cigarillo

And I know that you know

When it lies…

I like the natural

look of love

You know, the way it is.

I said I was tired

And you didn’t keep me

Up all night…

Almost like you recognized

I was a human being

With needs

Like sleep

To me, that is love.

But I am not

Romant-ick…

It makes me sick

Like if sex is good

You don’t always have to

Talk about it

You’re too busy

Doing it…

And love is like that

If you do love

True love

Not just constantly hot

New love…

It’s real.

Like a kitten, not a card

Like a baby, not a cupid

Like a grandpa, not a holiday

Like a real, live, rosebush

It lives because

You tend it

Like a garden

I water my garden

I don’t just

Write poems to it

Black And Queer

Are Not Just Trends

By Sumiko Saulson

Black and queer

Are not just trends

Fashion or make-up

You share with your friends

You feel persecuted as a goth?

Are you for real?

The identities of the marginalized

Are not for you to steal

When they said put away

Childish things

I didn?t know they meant

Childhood friends

When achieving dreams

For your community

Means your childhood ends

When you love and you care

But there is nothing there

That can replace the fact

That you have been back and forth

And here and there with them

To find in the end

You gotta stay black

Gotta stay black,

In the face of injustice

You gotta fight back

They tell you to use

Your inside voice

And feel under attack

They don?t understand

Your motivation

And you gotta know why

When they see racism

And social injustice

They just turn a blind eye

Black and queer

Are not just trends

You appropriate for a season

Until your need for them ends

They are on you for life

With out any choice

Your skin-deep

Your soul-deep

Your kin-deep

Your voice